Itasha: When Anime and Cars Collide (Part 1)

- the DREAM

- Jul 13, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 11, 2025

Diving into a fluffy cultural piece, we examine the history, cultural and technological influences that brought about the itasha. The waifu-rides that attract all kinds of eyes but has become far more than just fandom and cardom.

When you think JDM, it’s all boost gauges and sideways action or perhaps economic little Kei trucks and quirky cars. But beneath the screeching tires and carbon-fiber bravado lies another kind of underbelly—one lined not with turbochargers, but a school uniform or a suspiciously well-fitted maid outfit and questionable age disclaimers. Enter the itasha: literally “painful car,” and figuratively the most delightfully shameless subculture on four wheels.

Ready to unravel the bright, cringeworthy, wallet‑hurting—and wildly liberating—history of itasha in JDM culture? Buckle up. Today's article is a cultural love-story of 2 of Japan greatest exports: JDM cars and Anime (with Hello Kitty coming a very close 3rd):

In Part 1 (this article), we're doing a history dive, showing all the cultural roots from stickers to F1 podiums.

In Part 2 (next month), we're bringing it home to North America, looking at car-wrapping, the tech and the costs involved.

#1: Origins of the Name: From High-End Imports to Eye-Watering Wraps

If you thought “itasha” was just a quirky fan word slapped onto anime-covered Civics, think again. The roots of the term are tangled in both high-end imports and the relentless Japanese habit of bending language to serve cultural subtext.

Originally, “itasha” was a portmanteau of Itaria-sha (イタリア車), literally meaning “Italian car.” In the bubble-era 1980s, when Japanese wallets were swollen and import fever ran high, owning a Ferrari or Lamborghini wasn’t just flex—it was identity. These Italian cars earned the nickname itasha among enthusiasts, a slightly tongue-in-cheek nod to their exotic origin and spicy price tag (Yokogao Magazine).

Japan’s car culture has always been an extension of self. In the post-war period, the car wasn’t just a means of transportation—it was a canvas. From VIP luxury sedans with their slammed air suspension to the snarling bosozoku bikes and their oversized fairings, Japanese vehicles have long communicated who you were and what tribe you belonged to. This was the 1980s and 1990s—Japan was flush with otaku energy, and car culture was just beginning to co-mingle with nerd-dom. So when otaku culture—once a private, even shameful obsession—began bleeding into public life, it was only a matter of time before someone’s love for Dragon Ball ended up on a bumper.

But back then, nobody was wrapping an entire Civic in Sailor Moon decals. That would’ve been insane.

Instead, people started small.

#2: The Sticker Era to the Full Wrap Revolution – How Comiket Launched a Thousand Itasha

Picture it: a Doraemon plushie suction-cupped to a rear window. A tiny Gundam pilot figure perched proudly on the dashboard. A sticker of Lum from Urusei Yatsura peeking out from a fender, more Easter egg than exhibit. These early expressions weren’t called “itasha” yet—they were simply another form of identity signaling. And in a pre-social media world, signaling mattered.

These early adopters may not have wrapped their entire rides in 2D waifus, but they were laying the groundwork for a new kind of automotive expression. In fact, some have compared this era to a kind of “pre-livery age,” where the accessories spoke louder than any paint job. As noted by Backroads Magazine, “Itasha’s true beginnings were nothing more than stickers and small decorations... rather than the full-liveried insanity it’s known for today” (https://thebackroads.co.uk/2020/02/03/itasha-the-twilight-of-clashing-worlds/).

... and just before someone @'s me for posting stuff from AliExpress, let me say 2 things: 1) I do not endorse (nor am receiving endorsements from) AliExpress 2) If you're getting stickers for your car, do the decent thing and buy from the original artists.

The sticker era also coincided with Japan’s explosion of consumer goods and hyper-niche merchandising. You couldn’t walk through Akihabara in the 1990s without being bombarded by capsule machines, limited-edition model kits, or vinyl decals of obscure manga characters. Car owners began to take advantage of this merch ecosystem, customizing their rides in ways that were inexpensive, reversible, and socially low-risk. After all, slapping a Sailor Moon sticker on your rear windshield was a lot less controversial than doing a full-body wrap of Rei Ayanami across both doors.

What’s fascinating is how this low-stakes experimentation mirrored broader shifts in Japan’s cultural confidence. As the anime and manga industries matured, and as being “otaku” became slightly less of a social death sentence, car owners began pushing the envelope. Stickers got larger. Plushies became installations. Hood-mounted figures appeared at underground meets. And soon enough, that cultural restraint gave way to boldness—an entire wrap, an entire character, an entire identity, splashed across every inch of your ride.

These sticker cars weren’t yet “painful”—not in the way the term itasha would later imply. They were quiet declarations. They were the manga-reader’s answer to the bosozoku’s roar. And by the early 2000s, thanks to advancing vinyl technology and a growing sense of public fandom pride, those whispers were about to become shouts.

(Sources: TheBackroads, Screenshot Media, Wikipedia)

It wasn’t until Comic Market 68 in August 2005 that the first full-vehicle itasha made its mark at the legendary doujinshi convention

Comiket: the Venue that Launched a Thousand Itasha

If the sticker era was a whisper, then Comiket 68 was a fireworks show. Onlookers at the Tokyo Big Sight convention center were greeted with something that, at the time, was unprecedented: full-sized, fully-wrapped vehicles covered in custom anime artwork. We’re not talking about a tasteful fender decal or a vinyl cutout of Pikachu in the corner of the rear window. These were full-body shrines on wheels.

Before this, cars had flirted with fandom. But in 2005, they married it.

Comic Market 68—or Comiket, as it’s affectionately known—is a biannual grassroots mega-event that gathers over half a million fans, artists, and cosplayers in one of Japan’s most intense displays of do-it-yourself culture. Held in August 2005, this legendary Tokyo doujinshi convention—already the beating heart of otaku subculture—was where the itasha concept went from underground hobby to full-on spectacle. According to reports from early attendees, this was the first documented public appearance of what we’d now call “full-wrap itasha”—vehicles completely immersed in 2D art, often from visual novels, eroge (erotic games), or then-new anime properties like Fate/stay night (Wikipedia). This is when itai (痛い) — “painful,” “cringe-inducing,” even “painfully expensive”— combined with sha (車, car). Itasha morphed into a slang for cars that hurt your wallet and your eyes (the good kind)

This era also coincided with major leaps in wrap technology. Previously, vehicle wrapping was a niche reserved for taxis, corporate fleets, or advertising trucks. But digital printing had come a long way. Suddenly, anyone with a little cash and access to a print shop could upload high-resolution anime art and receive custom-fit vinyl sheets, ready for application. DIY wrap kits proliferated on internet forums like 2chan and Akiba blogs, turning formerly amateur fandom into a practiced and polished sub-art form.

The impact was immediate. Car enthusiasts realized that with a bit of large-format printing, they could transform their daily driver into a love letter to their favorite character. Fans realized they no longer needed to confine their cosplay to their clothes—they could now cosplay via car. And the media realized something wonderfully strange was happening in otaku land. By 2007, Tokyo hosted its first dedicated itasha convention near Ariake, capitalizing on Comiket's momentum. The event, known as “Autosalone,” formalized what had previously been street show-and-tells into an annual rite of fan expression (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itasha, Wikipedia). Additionally, one of the biggest events you can attend is Itasha Tengoku (ie. Itasha Heaven). Dino DC tells and photo-documents that story better, so you should check out his article if you are after quick visuals and want the TD:DR video version!

One of the best video documentations of this phenomenon comes from Alexi Smith—aka Noriyaro—whose YouTube footage captures the energy and excess of events like Itasha Tengoku and the infamous Fuji Speedway gatherings.

And of course, these wrapped cars didn’t just stay parked. They cruised. They paraded! They infiltrated meets and circuits. These weren’t just cars. They were declarations on wheels.

By the end of the 2000s, what started as a clever sticker had become a movement. Whether on the streets of Akihabara or on the track in Suzuka, itasha had staked their claim—not just as part of otaku culture, but as a standalone icon within Japan’s custom car pantheon.

(Sources: Screenshot Media; Wikipedia)

#3: When Itasha Took the Track by Storm -Motorsport Meets Otaku

Distinctive colors (and eventually wraps) have always been a part of racing. Before Hatsune Miku (ask your kids if that reference is too old) ever drifted through Suzuka or wrapped herself across a GT3 car hood, race cars were already decades deep into their own love affair with liveries. Vehicle decoration—particularly in racing—has always been about identity, visibility, and, eventually, monetization. In the early 20th century, racing teams used national colors: British Racing Green, German Silver Arrows, and Italy’s iconic Rosso Corsa. But it was American stock car driver Richard Petty who introduced a revolution in branding when he ran his cars in his now-iconic “Petty Blue” mixed with corporate STP red, one of the earliest and most memorable examples of paint becoming brand (NASCAR Hall of Fame).

By the 1970s and ’80s, this idea had evolved into a marketing engine. Liveries became high-impact, mobile billboards, particularly in NASCAR and Formula 1. The success of Marlboro’s red-and-white McLarens (a la Prost and Senna) and the instantly recognizable yellow-and-blue Camel Lotuses weren’t just due to wins—they were memorable because of their appearance. That same logic trickled down into the commercial world: city streets soon hosted promo-painted delivery trucks, branded company vans, and wrapped city buses promoting seasonal TV releases. These were technically fleet vehicles, but in spirit, they were rolling advertisements—an early mirror of what itasha would become. By the 1990s, Japanese taxis and local anime tourism groups were experimenting with vinyl-wrap and sticker tech to signal their unique community identities (Tofugu; Wikipedia).

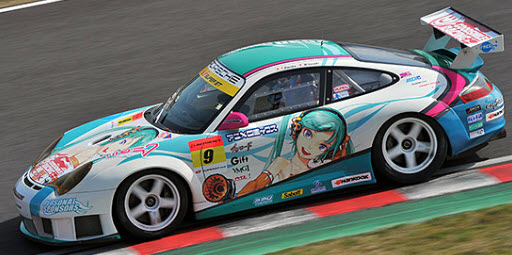

So when itasha began blooming into full-body character wraps by the mid-2000s, it wasn’t exactly a cultural anomaly—it was the natural next step in an ongoing visual arms race. The tools were already in place: motorsport liveries taught us how to make machines memorable; fleet graphics showed us how to blend utility with identity. All that was left was the otaku twist—anime instead of ad copy, fandom instead of sponsorships. And when Good Smile Racing brought a fully branded Hatsune Miku GT300 car to Super GT in 2008, the loop closed. Anime cars, once inspired by race cars, now were race cars.

#4: Good Smile Racing: Moe Torque - The Fast and the Fan-Service

Born in 2008 as a motorsports-offshoot of Good Smile Company—the famed maker behind Nendoroids and Figma figures—Good Smile Racing began by sponsoring the Studie GL@D team in Japan’s GT300 class with a full-body Hatsune Miku livery on a BMW Z4. This bold move, blending idol culture with speed, marked a world-first: an itasha design on a professional race car (Vocaloid Wiki; Goodsmile). This marked a significant moment: itasha wasn’t just for late-night drives anymore—it now had a lane in mainstream motorsport (Wikipedia).

Source: Goodsmile Racing US

Two years later, in 2010, Good Smile Racing officially split from their partner to create an independent entry in Super GT. They swapped the Z4 for a Porsche 911 GT3 initially, and by 2011, returning to BMW, they added a new driver: veteran Nobuteru Taniguchi, with ex-F1 racer Ukyo Katayama as team principal (Vocaloid Wiki; Wikipedia).

Despite being born from an anime figure company, Good Smile Racing didn’t hit the track for novelty—they came to dominate. Call it cosplay on wheels if you want—but it’s also pure racing pedigree. With Hatsune Miku on their hood and serious talent behind the wheel, they’ve become one of the most decorated teams in Super GT’s GT300 class. Their fusion of fan culture and high-performance engineering earned them three championship titles, podium finishes at the 24 Hours of Spa, and a defining presence at endurance races like Suzuka.

(Sources: Good Smile Racing; Wikipedia; Kaori Nusantara)

Fan-Powered Speed: Good Smile Racing’s Sponsorship System

Good Smile Racing isn’t just anime-branded—it’s fan-powered. Since 2008, the team has operated a unique and wildly successful Personal Sponsorship System, which allows individual fans to financially back the racing team in exchange for exclusive rewards. For as little as ¥5,000 (about $35 USD), supporters can receive official sponsor cards, merchandise, and limited-edition collectibles like Nendoroid Racing Miku figurines, umbrellas, stickers, and even branded apparel. Higher-tier backers—often paying ¥30,000 or more—may even have their name printed on the car’s livery or team race suit, depending on the season and campaign structure (Good Smile Racing; PreviewsWorld).

This model isn’t just symbolic. By 2011, over 10,000 personal sponsors had joined the movement, according to team reports, and the system has since become a cornerstone of how GSR operates year after year—serving as both funding engine and fan engagement strategy. It’s not uncommon to see fan forums and subreddits buzz during sponsorship launches, with discussions comparing merch bundles, season exclusives, and real-world impact. One Redditor described the model succinctly: “Much of it goes to the racing team itself. It’s crowdfunding, but with better rewards and waifus” (Reddit). Through this model, Good Smile Racing has built one of the most loyal fanbases in motorsport—not just people cheering from the sidelines, but literal backers whose cash fuels the car. It's grassroots racing in the most 'moe' way possible. When fans wear the team cap, wave Racing Miku towels at Suzuka, or unbox their sponsor-only Nendoroid, they’re not just spectators. They’re stakeholders.

This razor-sharp strategy—blending fan devotion with team financing—reinforces GSR’s identity: it’s the racing outfit driven by fans. And when your backers are proudly wearing your logo, turning up at races with merch in hand, and forming grassroots support squads, you’re not just racing—you’re rallying a movement.

From Itasha to It’s-Everywhere

The ripple effect was immediate. Racers and fans alike embraced the idea that automotive performance and fandom could coexist, even complement. Soon teams across grassroots N1 events and independent track days were adorning Nissan Fairladys, Honda Civics, and Subaru WRXs with character artistry. Itasha weren’t off-track curiosities—they were legitimate entrants, complete with timing stickers and sponsor logotypes.

Meanwhile, in 2008, Age Soft CEO’s Lamborghini Gallardo was splashed with hentai-inspired custom airbrush art—effectively bridging exotic super car culture with erotic fandom. Now, in fairness, Age Soft does publish dating sims and other **cough-cough** "dating adjacent" sims, so I guess you could argue that this is also a vehicle for advertising.

But either way, the result was breathtaking and viral. Media wrote about itasha as edgy, provocative, and sociologically rich (which is academic shorthand for “half of Japan’s car hoods are now thighs, cleavage, and pastel hair”). And once the genie popped out of that bottle like.... well,... a fan of any "dating adjacent" video game, there was no turning back.

This period inserted itasha squarely into the lexicon of performance meets and car culture archives. Suddenly, the same car that once hauled eggs to the grocery store now logged laps at Suzuka—painted in full gloss Manga panels and rolling art. This fusion cemented itasha as a fixture not just in photo blogs, but in paddocks, Paddock Pass programs, and commentator dialogue. The movement had crossed the barrier from “cute cars” to a legitimate facet of Japanese automotive culture.

#5 Weebs Without Borders

From one-off stickers to full-livery masterpieces, from underground meets to Super GT podiums, the itasha has done more than just evolve—it has multiplied, morphed, and gone mainstream. What began as quiet personal expression has become one of Japan’s loudest cultural exports—not because it’s polite, but precisely because it isn’t. Itasha are too much on purpose: too bright, too bold, too obsessive, too honest. And that’s why they work.

The itasha movement carved out space in a society that often discourages public display of private interests. But anime-wrapped cars didn't ask for permission—they took space on the road, at the track, and eventually, in the collective imagination. They became viral sensations, artistic statements, and rolling provocations. They may look like fanboy indulgence on four wheels, but they’re also performance art—and in some cases, high-performance art.

And now, the wheels keep turning. Across the Pacific, in places like Houston, Los Angeles, Toronto, and beyond, we’re seeing the next chapter: the rise of the North American itasha. These builds remix the visual language of Akihabara with the car culture of Cars & Coffee, SEMA, and Sunday night drift meets. From Senpai Squad GT-Rs to low-budget Civic waifus, the vinyl has crossed the ocean—and it’s not slowing down. That’s where we’ll go next.

Got a favourite waifu/husbando for your dream car? Running a wrap and want to share with pride? What are your throughts? Comment below!